In August 2013, nearly 7 tons of pangolins from Indonesia were seized.

from CNN read more: Pangolin-trafficking

It's impossible to say exactly where Lucky and the other trafficked pangolins in Vietnam came from. But there's reason to suspect Indonesia, the 253-million-person nation made up of thousands of islands that straddle the equator.

In August 2013, nearly 7 tons of pangolins from Indonesia were seized at a port in Haiphong, Vietnam. In 2008, almost 14 tons of pangolins, frozen, were seized in Sumatra, the westernmost island, likely bound for Vietnam or China.

The man responsible for that 14-ton bust -- I'll call him Q to protect his identity -- picked me up at the airport in Sumatra. He's a put-together guy who wears button-up shirts, parts his hair in the middle and listens to jazz.

He also leads a double life.

He works as an undercover wildlife investigator for an international organization.

His young children think he's unemployed.

Q has been able to pull off that deception because of personal connections. Someone in Q's network (I'm not saying exactly who) once was a tiger-trading and slaughtering kingpin. Ask him about it and Q matter-of-factly says that this man is partly responsible for the fact that there are only 400-some tigers left in Sumatra.

But Q is making good on that connection. He uses his link to a now-deceased trafficker to get access to criminal wildlife-trading networks.

And then he shuts them down.

He's had a surprising amount of success.

I asked Q to help me understand the supply side of the pangolin trade. Where do the pangolins come from, and how are they shipped for export?

He towed me into that world, which felt at times like I was being pulled into an episode of "CSI" or "Weeds." I hoped the whole thing wouldn't end up like "Locked Up Abroad" -- me in jail, or worse, left in the hands of cutthroat traffickers.

Q wasn't too reassuring on that front.

At breakfast before we set off to meet with one of the pangolin mafiosi, he dropped on the table a jar containing a dead, baby pangolin floating in a yellow liquid.

A trafficker we were going to meet gave this to Q as a gift, he told me.

Q plays every situation, dangerous or not, with a smile and a joke. But Q knew I would be taping the interview with two hidden cameras.

He knew what could happen if this guy noticed.

"Big boss," he kept telling me in heavily accented English. "Big boss."

Subtext: Don't end up like that pangolin in the jar.

Encounters with pangolin mafia, incident 1 of 2:

The first member of Sumatra's wildlife-trading mafia who Q helped me meet looked like Barack Obama -- cropped hair, coffee skin, a toothpaste-commercial smile. That lightened the mood a bit. I walked past his spiked gate, up the driveway and into his living room, which has a large rug with a lion's head on it.

The trafficker, whose identity I'm withholding since I did not identify myself as a journalist, displayed a strange fondness for pangolins for someone who admitted to buying them from hunters and arranging their transport to larger cities. (Q told him that I also was involved in the illegal wildlife trade in order to hold his cover).

He built an entire room for pangolins in his house, in the Lebong district of Sumatra, but he couldn't keep them inside, he told me.

[+] Click to enlarge

The good news: Some former hunters are now trying to protect the pangolin. The bad news: Pangolin is easy to find on menus in Hanoi. Some restaurants slit its throat in front of customers.

JM for CNN

[+] Click to enlarge

In February, a restaurant in Hanoi kept this pangolin floating in rice wine. CNN reporter John Sutter was told it was removed after authorities were called.

John Sutter/CNN

They kept digging their way out through the tile floor.

"Oh, I think this animal is very smart!" the trafficker said, lighting up.

This man seemed to think pangolins had video-game-like powers. He told me the pangolins tried to escape from his house by curling up into balls and then spinning with Sonic-the-Hedgehog speed to burrow through the floor.

He said they can hide underwater for upwards of 15 minutes without air.

And he told me their blood has magical healing properties -- four of them.

"My boss says if you want to make medicine from pangolins, you take rice wine and boil it with a baby pangolin, and put it in a jar," he said in a local dialect, which I recorded and had translated later. "You don't have to mix it with other ingredients, you just boil it with the wine and you put it in a jar. Every morning you drink one small cup -- and it can heal you from disease. There are four ways it will help: First, for skin disease. Second, it will make you always feel fresh. It will help you breathe easily (that's three) … and I forget what the fourth reason is."

I would let the four-reasons thing go, except that he kept going with it: "I guarantee you, if you drink that wine, you will get healed from those four diseases."

Right, four.

He said he's gotten out of the pangolin trading business recently because it's risky to ship them. He was trying to move pangolins by car from his town to Palembang for export (usually to Vietnam, he said). The car's tire popped on the way and police threatened to confiscate the 1-ton load of pangolins in the back. "We had to pay about 300 million (rupiah, or $26,000) to get the pangolins and car out of there," he said. He laughed about the bribe.

Police threw in a free spare tire as part of the deal.

"With money," he said, "you can make everything easy."

There was a time, perhaps a decade ago, when pangolins were so common in some parts of Indonesia that people literally hit them with their cars. Three such car-pangolin crashes were described to me on my trip.

From them I can draw two conclusions:

This never happens anymore because pangolins are so rare.

Pangolins are tougher than cars.

None of the pangolins died on impact. The drivers said they checked.

Encounters with pangolin mafia, incident 2 of 2:

"Would you like to see the snakes?"

That's a question that, in normal life, I would always say no to … 100% of the time. But on assignment in Sumatra, in a wildlife trafficker's living room, I had to say yes.

I kind of wanted to say yes.

The trafficker, the one who gave Q the pangolin in a jar, looked like every drug dealer you've seen cast for a U.S. TV series -- surfer shorts, button-up, short-sleeve shirt, slouchy-but-I'll-kill-you demeanor. He led me into his back hallway and opened the door to what appeared to be (or formerly was) a bathroom. Dozens of rice sacks were tied at the top and each, from my understanding, contained a live python. I didn't quite believe that until this man grabbed one of the bags and dumped out a 12-foot python at my feet -- my bare feet, by the way.

I jumped like a meerkat -- directly over the snake, which was slithering at me, and fast. The trafficker and my translator thought this was pretty hilarious.

Where do you go from there except back to the sitting room to talk about trafficking pangolins? From my chair by the door, I could see the trafficker's kids around the corner watching TV and playing with little-kid toys. One (no joke) was holding a helium balloon in the shape of a panda, an endangered animal.

Q explained to me later that this trafficker uses pythons as a cover for his pangolin shipments. He puts them on top, because pythons can be shipped out of Sumatra with a permit and under a certain quota. I asked the trafficker if I could see a pangolin (this was probably overly bold in retrospect) and he declined.

But he did make an offer.

"Yes, there are plenty of pangolins here," he told me, thinking that, because I'd come with Q, perhaps I wanted to strike up a deal. "If you have enough money, for one month, I could supply you with two or three tons" of pangolins.

He asked for an inflated price – the Chinese price, he said.

Three tons for about $790,000.

Some time ago, he would have accepted maybe a third of that.

But it's getting harder to ship pangolins out of Sumatra, he said, both because there's more police presence (thanks probably to the bust Q orchestrated in 2008) and because customers in Vietnam and China now demand live pangolins, for slaughter at the table, and live pangolins are more difficult to pack into cars and drive around.

Tellingly, none of that means the trade will stop -- it just means it's more expensive.

"I have connections at every level of the police force in the region," the trafficker said. "I have to pay them every month -- about 15 million" rupiah, or $1,300 total.

Learn to speak trafficker! In addition to having their own nicknames -- "Iron Face," "Golden Scales" -- wildlife traffickers also speak in their own code language.

A key, courtesy of Q:

"08" = whole tiger

"Yellow bamboo" = ivory

"CB" = rhino horn

"TH," or "tonti" = pangolin

"Jacket" = tiger skin

Ketenong, population 580, is squished between two picturesque national parks in South Sumatra Province. That makes it prime poaching territory.

No one here cared about pangolins -- never gave them a thought -- until a few years ago when a wildlife trader from Bengkulu came to town. Ruslan, a 58-year-old who used to hunt pangolin, remembers the man well -- and what he promised.

"You find pangolins, and I'll give you money."

Simple enough.

So Ruslan did.

A wiry man with porcupine hair and a raspy, Joan Rivers voice, Ruslan worked in the rice fields by day, then climbed into the forest at night to hunt pangolin. He didn't know it was illegal, but he got quite good at it.

Ruslan, 58, and another pangolin hunter, Ropi, a 29-year-old who wears a pink backpack, showed me one night what it's like to go on a pangolin hunt. Both men told me they're not currently hunting pangolin, but they took me into the forest to show me how it's done. I asked them not to actually trap any pangolins on my behalf.

Let me just tell you, pangolin hunting is hard work.

A few notes from my journal entry that night:

"Holy s***! That's work! Trudging through mud that's shin deep. There could be tigers or rhinos to chase you down. Looking for an animal some consider satanic. When you hit it with a flashlight (which we didn't) it looks like a ghost -- you see its red, beady eyes. Crossed rivers I don't know how many times.

I don't know why I didn't lead with the leeches. I only got one leech stuck to my shoulder, but my traveling companions all had more. One had seven. We were out in the forest for maybe two hours, patrolling like security guards with flashlights. It's almost impossible to watch where you're going and look for pangolins, which means you're often sliding down mud-covered mountainsides, getting stuck in tangles of ferns and vines and plants with spikes on them. I reiterate: This is hard.

"The second hunter climbed up a slippery cliff, hoisting himself up vines, chopping down other vegetation with a machete. The first grabbed my hand to pull me up to a (pangolin) nest -- shone light on the "tracks," which were so faint in the Martian red mud that I couldn't see them even with his guidance."

Ruslan helped me understand the experience by summing it up this way:

"If we were rich people, we wouldn't want to go into the forest to hunt pangolin."

We didn't find a pangolin, but the experience was enlightening. Pangolin hunting is the worst. And it hasn't made Ruslan and Ropi rich. They're not motivated by greed. They're not buying fancy cars -- any cars -- or big, showy houses. I went in both men's homes. Ruslan's cache of electronics includes a (non-smart) cellphone, a small TV and a rice cooker. Ropi lives in a humble wood home that appeared to have two rooms. Their village only got electricity two years ago -- and many rice farmers here only earn the equivalent of about $2 per day. This is a desperate place. Ropi told me he only considers going out to hunt pangolin again when he sees his two young children, a boy and a girl, and realizes that, without the extra income from the hunt, he doesn't have enough money to buy them milk.

People in this part of Indonesia once saw the pangolin as cursed.

Find one in your house and someone in your family might die soon -- or the house might burn down. Some people, according to Q, even believed that pangolins were mystical, almost satanic. If lightning struck, they could disappear in a flash.

Now those beliefs are gone.

International demand has infected this place.

"I think when you find the pangolin you are lucky," Ropi told me.

"You can change the pangolin (into) money."

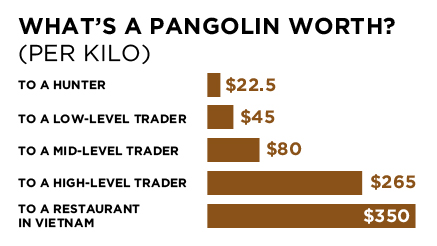

Estimated value of a pangolin:

To a hunter in Indonesia: $18 to $27 per kilo

To a low-level trader in Indonesia: $45 per kilo

To a mid-level trader in Indonesia: $80 per kilo

To a high-level international trader: $265 per kilo

To a restaurant in Vietnam: $350 per kilo

I told one of the hunters, who had been getting $18 to $27 per kilo for pangolin, what restaurants in Vietnam charge. "Wow! That's a very fantastic price!" he said.

Then he thought about it.

"I think that's unfair."

My thinking about pangolins got caught in a loop after visiting the hunting village of Ketenong. Is better enforcement of the law the solution? I didn't like the idea of cops arresting people like Ropi and Ruslan, the men in the food chain with the least to gain, although I did hear that the threat of arrest is an effective deterrent.

Enforcement should focus primarily on the international networks – on breaking down the barriers that insulate the real players in this trade from arrest.

Part of that means rooting out corruption.

Part of it means hiring more people to patrol the forest. Rangers I met told me their numbers in Sumatra are ridiculously inadequate to protect wildlife here.

But what about other solutions? Education? It seems like a hard sell to think that explaining to people why pangolins are important -- something I have enough difficulty articulating after nearly two weeks of talking about them -- would suddenly change the minds of big-boss wildlife traffickers or ground-level poachers.

At least that was my skeptical view before I met a man named Suryatin.

Suryatin has managed almost singlehandedly to turn a village of pangolin hunters into pangolin protectors. And he's done it by gently coaxing people to Do the Right Thing by supplying them with better information about pangolins.

"If the forest is destroyed, life is also destroyed," he told me.

"Enforcement isn't effective out here. People need to know why you're not allowed to hunt pangolin," he continued, before offering the most concrete ecological argument for the pangolin's importance I'd heard. "Next door is a rubber plantation. Sometimes the ants eat the rubber trees. Why that happens is because there are no more pangolins -- so because of that, I try to convince people to let the pangolins live.

"Letting the pangolins live can help the rubber trees survive."

Where was this guy two weeks ago?

It's not just about the rubber trees, of course.

Suryatin, 63, and the 1,260-person town's mayor, Yendra, actually buy pangolins back from poachers if they see them leaving town to sell to a collector. They pay full market price, he told me, or about $22, because he cares that much about pangolins -- and because he sees it as a teaching moment. He takes the opportunity to explain to the would-be poacher that pangolins are unique and valuable -- a cornerstone of the local ecosystem, and that many industries would unravel without it.

"I just talk about why I care about wildlife and pangolins," he said, as if that's the simplest and most why-didn't-you-know-that solution ever. "People who buy the pangolins don't understand the benefits of the pangolins for nature."

It's working, but not for exactly the reasons he thinks.

I met one former pangolin hunter, Zainal Abidin, 54, who had one of these confrontations with Suryatin. He used to track pangolins by sound -- listening for the CRRRUK CRRRUCK CRRRUK of their scaly tails rattling against the tree branches -- before spotting them with a flashlight and, sometimes, clubbing them on the head. He told me he heard Suryatin's arguments about the pangolin's ecological value, and he understood. "Pangolins are interesting animals," he said. "Pangolins are just like humans; if the pangolin goes extinct it will affect the humans, too." But there were other factors in his decision to stop poaching: He is getting older, for one, and hunting pangolin is hard. Jail time is part of it, too.

But he also found another job.

When the economic incentive to hunt went away, it was no longer a consideration.

Education is an important part of the solution, but people also need jobs.

That's certainly something Suryatin can understand.

He got on this enviro kick several years ago when he received training from World Wildlife Fund, to start a tree nursery to help in reforestation efforts. He's done very well for himself, planting 5 million trees since 2003, he told me. He ended up buying the land across from his greenhouse because it's home to an enormous "root tree" where pangolins are known to nest, and where people used to hunt them.

If he owned the land, he thought, he could stop the poaching.

The root tree is a sight -- a tangle of vines that's easily three stories tall and as wide as a small house. Think of the tree from "Avatar" or something out of "Fern Gully."

It's that spectacular.

Suryatin calls it -- and I'm not kidding -- "The Tree of Life."

I had no idea I would meet Suryatin when I traveled out to his village, which is called Karang Panggung and is the closest thing I can imagine to a Sumatran enviro-utopia.

I thought I was traveling there to go on another pangolin hunt.

But that's not happening here anymore -- not much at least.

I talked with several people who expressed Suryatin's enthusiasm for nature. And I kind of fell in love with the place. I spent part of an afternoon taking photos with kids who were playing volleyball. They practiced their English on me: "Good morning I love you!" Almost every home seems to have potted trees out front, because many residents are helping in reforestation efforts.

So, instead of going on a pangolin hunt on my last night in Sumatra, I decided to take several people from the village with me to the Tree of Life.

I hoped we could see a pangolin in the wild.

Headlamps and flashlights in tow, we walked over to the tree around 8:30 p.m.

I asked one of my companions what other animals we might find out here. "Oh, tigers and leopards," he said. "You can see leopards in the secondary forest like this."

Great, I thought.

Tigers by dark.

The first hour was marked with lots of activity. One man climbed at least 20 or 30 feet into the tree to look for a pangolin that turned out, fittingly, to be a chameleon, the master of disguise. Some of us paced circles around the tree. Others walked the nearby forest, panning our lights like prison wardens. At one point, there was a faint light moving among the roots. A pangolin eye? Nope, lightning bug.

Around 10 p.m., we decided to have a seat and wait.

"Everyone turn off your flashlights," said Q, who still was traveling with me.

"Let's try being silent."

The next hour and a half was one of the most magical periods of my trip to Southeast Asia. I looked around, checking for pangolins and leopards, then lay down on my back and listened. The jungle will play music for you if you let it. An owl hooted on the upbeats; birds in the distance sounded like they were shooting lasers in video games; frogs squeaked like chew toys; and something behind my right ear sounded roughly like a car with an ignition struggling to fire.

(Please be a tiger. Don't be a tiger.)

The longer we were quiet, the more layers of sound revealed themselves. Sumatra is home to incredible plants and animals -- to elephants, rhinos, orangutans and the largest known flower in the world, Rafflesia arnoldii, with a bloom 3 feet across. All of those icons of nature are featured on national park brochures and Wikipedia pages. But in the echoing silence of that night, I was reminded of why the diversity of life matters.

The insect string section. The faint WHOOP WHOOP of the gibbon.

All of them are needed for the song to continue.

We've discovered and named perhaps 10% of the species that exist on this incredible planet, according to Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson. The unknowns are mostly the little guys -- the fungi, bugs and microbes. For me, the personal list of "unknowns" included the pangolin. It was new to me at the start of my journey.

Who doesn't want to live in a world where those discoveries are possible -- where the planet is full of possibility and wonder?

The alternative is awful: Knowing that we live in a place that is continually getting less diverse, less interesting, less capable of supplying humanity with scientific discoveries and medicines and better/stronger materials.

And, most importantly, less capable of supporting life.

The planet, like the pangolin, is surprisingly fickle.

"As extinction spreads, some of the lost forms prove to be keystone species, whose disappearance brings down other species and triggers a ripple effect," Wilson wrote in his 1992 book, "The Diversity of Life." "The loss of a keystone species is like a drill accidentally striking a power line. It causes lights to go out all over."

Perhaps that could be the case with pangolins.

Too little is known to be certain.

7 ways to help save the pangolin

A group in Vietnam will make a pangolin public service announcement if it raises $5,000 from CNN readers.

Read full story »

But everything in the natural world is connected. All of it matters. As one wildlife crime expert, Crawford Allan, put it to me: What's the point of saving Mona Lisa's smile if they rest of the painting is gone? That's the perfect metaphor for what's happening with the wildlife trade. Advocates have become so focused on nature's celebs -- the rhinos, the elephants, the tigers -- that they've neglected the bigger picture.

It's easy to ignore a species like the pangolin.

But we do so at our peril.

At first, lying there on the ground, I was telepathically willing a pangolin to emerge from the dark. Come on pangolin -- this would be the perfect way to end this story. Us meeting out here in the wild, under the "Tree of Life" no less. I need an ending here!

But the more we waited, the more at peace I was with the idea that I likely never will see a pangolin in the wild. Right then, under the tree, that seemed perfect. Not just OK, but better. I knew from what Suyratin and the others had told me that at least two pangolins actually do live in the tree. If they're smart enough to hide from us, they're probably better off than the pangolins in Vietnam, whose developed need for attention has cost them their freedom. These pangolins are wise -- and they're lucky. They live in a village where, even if they did present themselves, they would be protected. People here realize the world is a better place with the pangolin -- a little stranger, a little more wonderful. They're protected because they're understood.

That's the best the lowly pangolin can hope for.

And that's actually quite a lot.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| PangolinWorth.jpg | 74.95 KB |

| pangolin-map1.jpg | 140.8 KB |

- Editor1's blog

- Login to post comments