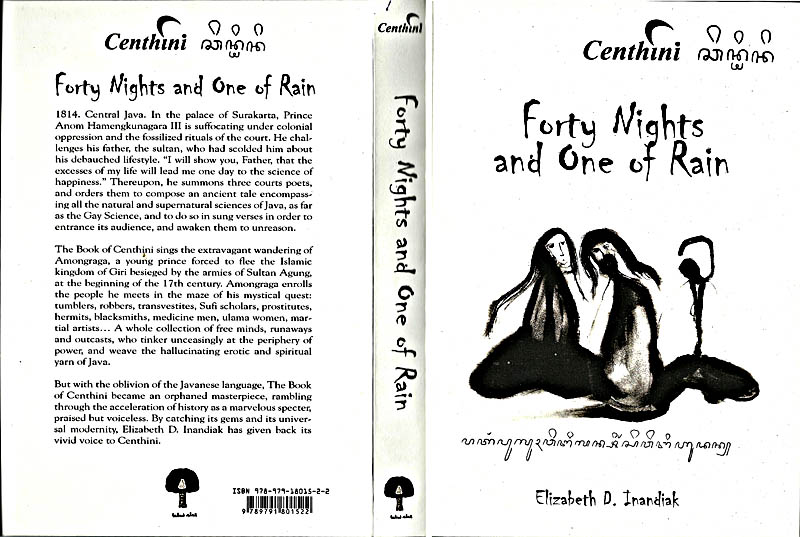

Centhini Forty Nights and One of Rain by Elizabeth D. Inandiak

---order from Elizabeth D. Inandiak directly, Elizabeth ships world wide.---

Writer Inandiak mirrors Javanese tradition

BY ACHRIEL, ON MAY 22ND, 2004

By Kunang Helmi-Picard

When Elizabeth Inandiak received the 2003 Literary Prize for Asia in March for her translation and adaptation of the early 19th century Javanese tale Serat Centhini, she was thankful that her parents were on hand.

Centhini dates back to 1815, when this immense compendium of hermetic knowledge in the form of a suluk (mystic poem) was inspired by crown prince Anom Amengkunagara III of the Surakarta royal palace. Under the auspices of the royal patron and future sultan Paku Buwono V, the court scholars Yasadipura II and Rangga Sutrasna began to compose the 4,000 pages distributed in 12 volumes in the true spirit of the Surakarta classical literary renaissance prevalent at the time.

The encyclopedic work encompasses art, music, divination and erotic knowledge, together with religious speculation and mysticism. It is enrichened by expressions, verses and allusions in Sanskrit, Arabic and Kawi (ancient Javanese).

see video Centhini: 40 Nights and One Rain

A very brief summary of the Surat Centhini

The Jakarta Post, Jakarta | Life | Sun, May 01 2005, 4:06 PM

The Serat Centhini dwells on the three children of Sunan Giri: Jayengresmi, Jayengsari and Rancangkapti. Fleeing the Sultan Agung's troops led by Raden Pekik, who burn down their house, the three siblings become separated and as a fugitive, Jayengresmi studies ma'rifat, the highest knowledge of mysticism, and starts to call himself Syekh Amongraga. The siblings make new friends and learn a lot from their experiences on the road. Some of these experiences related to Amongraga's delinquency, are told in the first book, Forty Nights and One of Rain. Finally, Amongrage gets married to Tembangraras, the daughter of an Islamic cleric, Ki Permana. Forty days after their wedding day, the couple has not yet had sex although they stayed completely naked in their bridal bedroom. All this time, Amongraga continued to teach his wife the ""essence of love."" -

Inandiak's version of 'Serat Centhini'

The Jakarta Post, Jakarta | Life | Sun, May 01 2005, 4:06 PM

Serat Centhini is a complete Javanese classical literary work. Compiled in the first half of 19th century, Centhini is to date the most complete encyclopedia about Java. It contains the paradoxes in life about virtues originating in Islam and gives explicit sex education to laymen in a manner that many modern scholars still find pornographic.

While providing moral teachings, the Centhini also details a large array of procedures involving traditional rites, auspicious days and how to treat nature. It gives, for example, a detailed method of how to properly fell a tree in a forest so that a disaster can be warded off.

Many literary experts are reluctant to translate the Centhini, arguing that the language used is too vulgar, particularly when it describes sexual intercourse, ranging from the conventional sex to sodomy. Reportedly, this ""pornographic"" part was written by Pakubuwono V himself, who sat on his throne for only three years and then died of acute syphilis.

Although it was Pakubuwono V, the King of Surakarta, that took the initiative to write Centhini, the process to create this classical literary work involved three palace poets: R.Ng. Ranggasutrasna, R.Ng. Yasadipura II and R.Ng. Sastradipura. The three of them, reportedly had to conduct their research throughout Java and studied literary works produced by all Java sub-cultures.

Having been well-kept in the palace and in the state's archive building for close to two centuries because it was feared that it would stir controversy among its readers, Serat Centhini can now be accessed by the common reader.

Unusually, it has been popularized by a foreigner that fell in love with this Javanese classical literary work while she was writing about Javanese mysticism.

Elizabeth D. Inandiak, a French poet-cum-journalist, was working in journalism in Indonesia in the early 1980s when she became interested in this ancient masterpiece.

Inandiak was in Indonesia to write a overview about mysticism. A well-traveled writer with an obvious thirst for cultural knowledge, Inandiak had already visited Tibet and met the Dalai Lama and gone to Bangladesh to meet local priests there. She was in Indonesia, interviewing the farmers and grave caretakers on the ancient slopes of Mount Merapi in Central Java, when she discovered the Serat Centhini. Actuel, a French monthly magazine published in Paris, was sponsoring her journalistic work.

""The Centhini charmed me greatly. I fell in love with this work just like a woman falling in love with a handsome guy,"" she told The Jakarta Post.

This interest did not come to nothing. In 1996, when attending a dinner at the residence of Thierry de Beauce, the former French ambassador to Indonesia, Inandiak received an offer to undertake a major project of translating this literary masterpiece. The ambassador, who was equally interested in Serat Centhini, funded the translation project, which took a full seven years to complete.

Fascinated by this ancient literary work, Inandiak knew she had to find out more about it and examine the manuscript in its original form. Inandiak only had in her possession the Latin transliteration of the Serat Centhini, which was originally written in the ancient Javanese alphabet.

Unfortunately, Inandiak's knowledge of old Javanese was not good and there was little supporting literature to help understand the work better. A summary of the content of the Centhini, made by Sumahatmaka in 1931, is in Javanese and the Indonesian edition of this summary was published by Balai Pustaka in 1981.

Luckily, she met an academic, Prof. Dr. H. Mohammad Rasjidi, who became an important resource for the project. Rasjidi, a former minister of religious affairs during Soekarno's times, earned his PhD in Philosophy in 1956 from France's Sorbonne University with a dissertation about the Serat Centhini.

Inandiak enlisted Rasjidi's help and returned to France, exploring the collection of books and dissertations in the Sorbonne University library.

The door to a better understanding of the narrative was wide open. ""I became optimistic that I could understand Serat Centhini,"" she said.

Another constraint emerged. It was not easy to find the right translator for the work. Many linguists and literature scholars refused when Inandiak asked them to take part in the translation. They generally argued it was taboo to translate this work because it dwelt on sexual matters in what they considered a highly vulgar manner. The only person who was ready to help her was Sunaryati Sutanto, a lecturer in the School of Literature at Sebelas Maret University in Surakarta.

Inandiak's cooperation with Sunaryati was eventually highly fruitful. She finally completed the translation of Serat Centhini into French, which was published in October 2002. It appears as a 466-page book, excluding footnotes and appendices, published by Le Relie under the title Les Chants de l'ile a Dormir Debout.

Inandiak is also having a fuller version of the book published in Indonesian, which is coming out in four titles. The first title, Empat Puluh Malam dan Satunya Hujan (Forty Nights and One of Rain) was published early last year. The second title, Minggatnya Cebolang (The Wife Runs Away), was launched in Surakarta later that year in April.

The remaining two titles will see the light of day later this year. They are Yang Memikul Raganya (The One Shouldering His Own Body) and Nafsu Terakhir (The Last Lust). ""I had to divide the work into four volumes so that it would not be too thick. I want every Indonesian to read this work because it is really an extraordinary literary achievement,"" she said.

Inandiak's obsession has also given her accolades. Last year, the French version of the book was named by Best Asian Book in 2003 by the French Government.

In her version Inandiak retold the Serat Centhini, which, originally contains 4,200 pages, 722 verses and over 200,000 stanzas, in a far slimmer book. Why is her version much thinner? Inandiak says, ""I did not include all the encyclopedic elements.

- Editor1's blog

- Login to post comments