How Indonesia’s gigantic fires are making global warming worse

UPDATE: Emissions from Indonesian fires have continued to rise since this article was published and now are estimated to be roughly equal to Japan’s annual carbon dioxide emissions. See here.

Experts say that along with dramatic global coral bleaching, thousands of fires across Indonesia represents the next sign of an intensifying global El Niño event. And the consequences, in this case, could affect the entire globe’s atmosphere.

That’s because a large number of Indonesia’s currently raging fires are consuming ancient stores of carbon-rich peat, which is found in wetlands featuring organic layers full of dead and partially decomposed plant life.

This year, the very smoky peat burning has been simply massive — the fires are estimated to have caused $ 14 billion in damage so far, and are causing hazardous air conditions in much of the area, including nearby Singapore. Millions of people have been affected, and 120,000 have sought medical treatment for respiratory illnesses, according to Weather Underground’s Jeff Masters.

Indeed, the 2015 Indonesian fire season has so far featured a stunning 94,192 fires. That’s more Indonesian fires than at the same time in 2006, a banner year both for fires and also for their carbon emissions to the atmosphere.

Those emissions are more than large enough to have global consequences. Indeed, according to recent calculations by Guido van der Werf, a researcher at VU University Amsterdam in the Netherlands who keeps a database that tracks the global emissions from wildfires, this year’s Indonesian fires had given off an estimated 995 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions as of Oct. 14.

That’s just shy of a billion metric tons, or a gigaton.

The number is an estimate, of course, and subject to “substantial uncertainties” — but it’s also based on a well-developed methodology for estimating wildfire emissions to the atmosphere based upon satellite images of the fires themselves and the vegetation they consume.

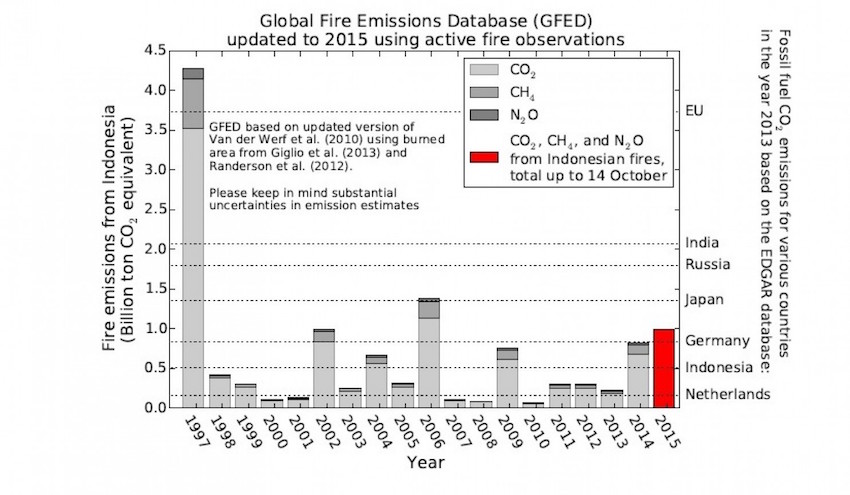

“Fire emissions are already higher than Germany’s total CO2 emissions, and the fire season is not over yet,” says van der Werf. He provided this figure, which allows you to compare how much carbon dioxide and other emissions Indonesian fires have put into the atmosphere each year since 1997 with the annual fossil fuel emissions profiles of various countries (including Indonesia itself):

Credit: Guido van der Werf, VU University Amsterdam.

As you can see, 2015 is already a very notable year — and it could get considerably worse. Van der Werf says he thinks that for total Indonesian fire emissions, 2015 may ultimately nestle somewhere between 2006 and the truly catastrophic year of 1997.

During that year, according to scientists who studied its aftermath, fire emissions from Indonesia alone were “equivalent to 13–40% of the mean annual global carbon emissions from fossil fuels.”

And while the emissions from wildfires in many parts of the world are at least partially offset as trees and vegetation subsequently grow back and pull carbon back out of the air again, that’s not so much the case in Indonesia. “In Indonesia, what’s burning is for the large part, peat layers that have been deposited over thousands of years. So this is really a net source of emissions just like fossil fuels are,” says van der Werf.

Thus, peat emissions are, in a sense, similar to Arctic permafrost emissions — built up over vast stretches of time, the carbon contained in thawing permafrost is also a new addition to the atmosphere if emitted.

Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo inspects a peatland clearing that was engulfed by fire during an inspection of a firefighting operation to control agricultural and forest fires in Banjar Baru in Southern Kalimantan province on Borneo island on September 23, 2015. ROMEO GACAD/AFP/Getty Images

What the severe Indonesian fire years of 1997, 2006, and 2015 all have in common is that they were El Niño years. El Niño is a critical factor in exacerbating Indonesian fires, because it tends to deprive the islands of needed rains and drive drought conditions.

Indeed, the Indonesian fires are “one of the first severe impacts of the strong El Niño that has been developing over the last year,” according to Columbia University’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society. And that also means the trouble probably isn’t over yet. A current forecast suggests “a strong likelihood of drier-than-normal conditions over broad areas of northern South America, the Caribbean, Indonesia and the Philippines” through December.

But it’s really the combination of El Niño and certain agricultural practices — characterized as “slash and burn” by NASA — that is at play here.

According to Susan Minnemeyer, who is the mapping and data manager for Global Forest Watch Fires, a project of the World Resources Institute, the blazes are the result of using fire itself to clear land for agriculture, as well as the draining of peat bogs and swamps – which makes them able to light up once they are dried out.

“The forests in Indonesia are generally not flammable, so these fires are virtually all caused by people, or land clearing,” says Minnemeyer. She adds that there is “little enforcement and little capacity to actually put them out once they’ve started.”

The total Indonesian fire emissions, says van der Werf, will show up in atmospheric measurements of carbon dioxide this year — and may even draw attention at the climate meetings that begin next month in Paris.

After all, according to the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, as of 2011 the world only had about 1,000 more gigatons of carbon dioxide to emit to the atmosphere if we want a two-third chance of keeping warming below 2 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial levels.

Chris Mooney reports on science and the environment.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| imrs-1.php1_.jpeg | 90.62 KB |

| imrs.php1_.jpeg | 100.71 KB |

- Editor1's blog

- Login to post comments